|

JOHN DAVIES

MEREWEATHER in AUSTRALIA

His posthumous connexion with FREDERICK ROLFE

|

1. In Australia

John Davies Mereweather was born in Bristol in 1816, son

of John Mereweather and his second wife Anna Maria

Davies. Both came from lines of craftsmen, shopkeepers

and traders. But young John had other interests. In 1839

he entered Oxford University. He graduated BA in 1843,

and was ordained deacon in St Faith's Church, London, in

1844. Then he was the curate of various parishes

until he decided to emigrate to Australia. This resulted

in two books:

- Life on Board an Emigrant Ship: being a Diary

of a Voyage to Australia (London, 1852);

- Diary of a Working Clergyman in Australia and

Tasmania, kept during the years 1850-1853

(London, 1859).

Mereweather is a shrewd observer, and the books are

filled with vivid detail of people met and things seen

while he travelled, this way and that, through an

inhospitable country. The books are still well worth

reading.

After a

138-day voyage from

Gravesend and Plymouth in

the Lady MacNaghten,

Mereweather arrived at

Adelaide on 16 June 1850.

"Adelaide strikes me as a

very miserable and squalid

place. Wide streets are laid

out, but there are few

houses in them, and those

few are mean and wretched;

the roads are full of holes,

receptacles of dust in

summer and mud in winter;

public-houses abound, and

drunkenness seems everywhere

prevalent." (Diary, p. 2f).

After ten days in Adelaide,

the Melbourne-bound

passengers boarded the

See Queen with

destination Port Phillip.

On 13 July 1850

Mereweather saw "the Bishop

of Melbourne (Dr. Perry), a thin and very acute-looking

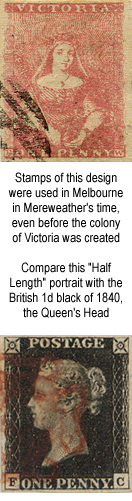

prelate. Bought a Queen's head for a letter. The

portrait of her Majesty is a wonderfully coarse

production of art, very much like a public-house sign

reduced." (Diary, p. 20)

For two months, Mereweather explored Melbourne and the

surrounding area. Among other things he was "initiated

in the mysteries of squatting" (Diary, p. 39), and he

was surprised to find that a squatter's life was not at

all as dismal as he had imagined.

It was in Tasmania that Mereweather found his first

employment, in October 1850. He was happy in the diocese

getting on well with his bishop and fellow ministers; he

was popular with his congregation. But then a squatter

from New South Wales called upon Mereweather and begged

him to act as chaplain in the uninviting remote parts of

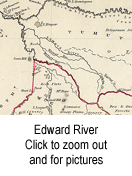

the Edward River district: "No clergyman had as yet been

found, he said, to undertake the arduous charge. I

determined to go there." (Diary, p. 84f)

On 15 May 1851 Mereweather travelled north from

Melbourne on horseback. After four days he crossed the

Murray, and, having entered his district, he immediately

took up his clerical duties: "Baptized a child. Held

Divine Service in the wool-shed. Twenty persons attended

..." (Diary, p. 90). On 24 May he was glad to set up his first

headquarters at Moolpa on the Edward River, after having

ridden 280 miles (p. 93). The district allotted to

Mereweather was enormous, stretching from the South

Australia boundary in the west to Albury in the east

(over 500 km). "... it is my duty to visit from station

to station, to hold morning and evening prayers, and to

endeavour to impact spiritual knowledge and religious

consolation to the white people scattered up and down in

this wilderness. May God grant me power to do it as I

should! I am not sent as missionary to the blacks, but I

shall study their character closely, and prevent the

publicans from giving them fermented and spirituous

liquors." (p. 110)

After having made a tour of part of his district,

Mereweather writes on 23 July: "I feel convinced that it

is absurd for any clergyman to undertake the pastoral

charge of this district, unless he be possessed of an

iron constitution and great patience; and be cheered by

religious enthusiasm. He must combine physical strength

with moral determination, and above all, he must look

for approval to a higher Power than his fellow-men." (Diary,

p.

121)

At Deniliquin, Mereweather was harassed by

the irreligious superintendent of the Royal Bank

sheep-station who "had advised his people to bring

up a large flock of weaning ewes close to the

wool-shed as soon as I should begin the Service, so

that their bleating might prevent my being heard."

(Diary,

p. 149)

Moreover, the shearers were amusing themselves with

horse racing, and Mereweather had to wait for three

heats to finish before he could start. And back at the

inn, he found a mob of men savagely drunk.

On 28 July 1852, after returning from a more than

month-long expedition, Mereweather learnt that he had

been appointed to the district of Surry Hills in Sydney

(Diary, p. 205). He held his first service there on 16 October

in the Darlinghurst Court-House; about seventy persons

attended, their behaviour being most exemplary, and

Mereweather was pleased even if he suspected that many

had come out of sheer curiosity (p. 223f). He started a

Sunday school and organised a choir which he was very

proud of.

Many years

earlier, Mereweather had

written a Song called See

Love's web around thee

weaving. This poem was

published in Sydney by W. J.

Johnson & Co. with music

composed by Miss Murphy.

After less than one year in Sydney, the entry

for 21 August 1853 abruptly states: "I grieve much that

the shaken state of my health, consequent on my

privations in the bush, will compel me soon to

relinquish all that I have worked up here with so much

labour, and to return to England." (Diary p. 260) Four days

later he sails out of Sydney bound for England.

|

|

|

|

2. The Frederick Rolfe connexion

The Desire and Pursuit of the Whole

(London, 1934) by Frederick Rolfe (Baron Corvo) is based

on Rolfe's life in Venice, mainly in 1909. The book's

subtitle is A Romance of Modern Venice, and much

of its charm lies in the depiction of Venice and the

lagoon. Many characters are easy to identify. Nicholas

Crabbe, the hero, is of course Rolfe himself. Exeter

Warden (in Rolfe's manuscript and in later editions: Londonderry Bagge) is Canon

Lonsdale Ragg, one of the many contemporaries lampooned

by Rolfe. Also for very minor characters Rolfe used

models from real life. And I venture to say that John

Davies Mereweather, once English Chaplain in Venice, has

inspired Rolfe in more than one way, even if he died

many years before Rolfe arrived in Venice.

In 1855 Mereweather settled in Venice. He was Chaplain

to the English residents there, a post he held until he

retired in 1887; he died in Venice in 1896. He had his

quarters in Palazzo Contarini Corfù. For a more detailed

account, click on the Home link above.

Mereweather loved Venice, its cultural heritage, its

beauty. He published Semele; or the Spirit of Beauty

: A

Venetian Tale (London, 1867). Semele of Greek mythology

is turned into an orphan daughter of noble Anglo-French

lineage. She explores the city and the lagoon giving the

reader something of a guided tour, often away from the

tourist areas. For details, click on the Semele link

above.

Mereweather also published three clerical tracts and a

short play in verse:

- La Chiesa anglicana e l’universale unione

religiosa / The Anglican Church, and universal

religious union (Bergamo, 1868 / Bristol,

1870), a pamphlet against the Papacy;

- On Weekly Communion and Faith in Church

Ordinances (Venice, 1869), objections to

evolutionists;

- The Seven Words from the Cross

(London, 1880), a pretentious piece combining

religious zeal with poetic ambition;

- Bacchus and Ariadne / Bacco ed Arianna

( London, 1891 / Venice, 1895), a play.

The post as English Chaplain in Venice

1905-1909 was held by Canon Lonsdale Ragg. It is reasonable to

believe that Ragg owned at least some of his

predecessor's books and also The Colonial Church Atlas

(see below). If so, he could have lent these to Rolfe,

or Rolfe could have found them when he spent some time

in Ragg's apartment in Palazzo Contarini Corfù (Desire, p. 212); Rolfe would

have had the opportunity to rummage through Ragg's

belongings which were being crated for shipment to

England. Some of Mereweather's books could even have

been available in Venetian bookshops in Rolfe's time.

Rolfe may well have read Mereweather's

Semele;

or the Spirit of Beauty: A Venetian Tale

when he wrote The Desire and Pursuit of the Whole: A

Romance of Modern Venice. In one of Rolfe’s manuscripts the

subtitle is A Venetian Romance.

It is

likely that Mereweather and his Australian

diaries form, at least in part, the background for the Sebastian Archer

story dealt with towards the end of Chapter XV of Desire

(p. 156f): "Sebastian Archer, a nice boy stupidly

misused by ultra-religious relations was scrapped (at

eighteen) into the dust-bin of Australia. His aim had

been the episcopalian ministry; and he never lost sight

of it. He was a large healthy athletic intelligent witty

fellow, clean to look at and good enough for anyone's

society. His job was to build a career out of nothing

with his naked hands. ... Squatter parents liked him:

his pups adored him: his principals left all to him

while they danced drunk in doubtful dwellings ..."

If Rolfe somehow saw the The Colonial Church Atlas, he

would have seen the maps of the various foreign

dioceses, e. g. Gibraltar and those of Australia, and he

would have noticed that they were all drawn and engraved

by one J. Archer. And if these maps were the source of

the surname, it would only be natural if St Sebastian,

condemned to be killed by arrows, supplied the Christian

name.

Immediately after the Sebastian Archer story, we learn

how Crabbe "stepped out into the gutter and wrote

feuilletons for farthing rags and short stories for

provincial syndicates – the type of trash which unearths

little lumps of guineas at unexpected moments

– the kind

of rubbish which the monstrous married mob reads,

believing it to be the work of a pair of themselves, and

he signed these 'Geltruda and Bevis Mauleverer'." This

clearly is "John Davies Mereweather". Rolfe, a Roman

Catholic, may have taken offence at Mereweather’s

anti-Catholic writings and decided to have a go at him in

the same way as he smeared living British residents in

Venice.

Thus Rolfe seems to praise Mereweather for his

documented achievements in Australia, only to turn against him for

his other pieces of writing.

OLE PEIN

Created on 30 November 2003

Updated on 8 December 2008 |

|

|

|