|

THE

PYRENEES

|

During the years

1836-1860, Mereweather recorded in a book of Memoranda

quotations in poetry and prose from various authors. He

also wrote down his own thoughts, poems and narratives.

In 1832, just before his sixteenth

birthday, Mereweather made a tour of the French

department of the Hautes-Pyrénées. The following

narrative was written down around the year-end of 1843

(pages 125-152). Paragraph breaks have been

inserted. Various

illustrations have been added. |

|

A Tour in the Pyrenees

Scorched by the sun who had exerted his most powerful

influence during the summer without intermission, and nearly

smothered by the dust, which after the excessive drought had

amassed itself to many inches in depth, I longed to leave

Bordeaux for a time to breathe the pure and cool air which

ever circulates among the Pyrenees, mountains abounding with

magnificence and sublimity of scenery scarcely to be

surpassed.

Accordingly, having taken my place some days previously, on

Tuesday the 21st of August 1832, I found myself at 7 in the

morning on the top of M. Dotezac’s heavy diligence drawn by

seven bulky but well fed grey horses with collars having

loudly tinkling bells attached to them.

I may here mention that the French seem very fond of all

sorts of noises, but especially of three, bells, drums and cur

dogs, one being scarcely able to pass a cart but he hears the

jingling of bells attached to the horse’s neck, scarcely able

to walk in a principal street but he hears the deafening noise

of a drum which some poor drummer is doomed to beat as he

walks for a certain space of time, and scarcely able to pass a

country dwelling but the shrill bark of some cur kindly awakes

him from any reverie into which he might have fallen.

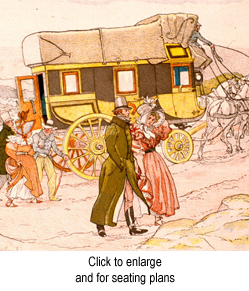

Well, I got on the coach early in the morning in high

spirits; but you must not imagine that the French

diligences resemble our little light vehicles which four

small but well bred horses can make to fly over the

ground at the rate of ten miles per hour. On the

contrary, the French coach has four distinct

compartments. The first of these with regard to price

and comfort is designated the Coupé. This apartment has

one side only, in fact just like a chariot, and will

contain three persons. The second and middle, called the

Intérieur, is made for six people, and though not so

expensive as the Coupé, yet contains very respectable

company. The third apartment, the Rotonde, is behind

all, contains about the same number as the middle one

and is usually filled by servants and people of the

lower class. Then comes the Banquet or Impériale on the

top of the coach which has a cover like a cabriolet to

be raised or let down at pleasure; it has also a leather

to come over the knees. This is intended for the same

class of persons as the Rotonde, but I prefer it to all

the others, as the passenger is able to have a perfect

view of all the surrounding country, and is completely

protected from the weather. Well, I got on the coach early in the morning in high

spirits; but you must not imagine that the French

diligences resemble our little light vehicles which four

small but well bred horses can make to fly over the

ground at the rate of ten miles per hour. On the

contrary, the French coach has four distinct

compartments. The first of these with regard to price

and comfort is designated the Coupé. This apartment has

one side only, in fact just like a chariot, and will

contain three persons. The second and middle, called the

Intérieur, is made for six people, and though not so

expensive as the Coupé, yet contains very respectable

company. The third apartment, the Rotonde, is behind

all, contains about the same number as the middle one

and is usually filled by servants and people of the

lower class. Then comes the Banquet or Impériale on the

top of the coach which has a cover like a cabriolet to

be raised or let down at pleasure; it has also a leather

to come over the knees. This is intended for the same

class of persons as the Rotonde, but I prefer it to all

the others, as the passenger is able to have a perfect

view of all the surrounding country, and is completely

protected from the weather.

|

However! To return to my tour. Having passed through

Castres and Langon, we soon came into the department of the

Landes which may be distinguished from that of the Gironde by

its black, marshy and uncultivated soil with few trees. The

shepherds here use high stilts to traverse the swampy

pastures, so that when I saw one of them stalking after his

flock, he put me in mind of Polyphemus. When Buonaparte passed

through this department on his way to Bayonne, the inhabitants

formed a guard of honour on stilts to escort him through their

country.

Towards evening, in the midst of a tremendous thunderstorm,

the diligence arrived at Mont St Marsan, a pretty considerable

town halfway between Bordeaux and Pau. In the morning the

change of scenery announced our arrival in the department of

the Basses Pyrénées [Pyrénées-Atlantiques]. The country now

began to appear more luxuriant, more cultivated, and not so

flat as the Landes; the cottages also were more numerous.

These have at a distance a very pretty effect, but only at a

distance, for on a closer examination they are found to have a

very wretched appearance, which with the addition of a pig and

some dirty children amusing themselves all in the strictest

amity before the door, gives them the air of an Irish

cabin.

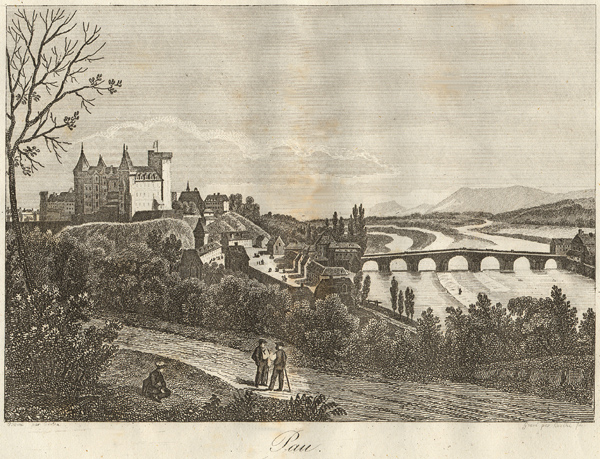

At last, after a very hot ride, and almost choked by the

dust, I arrived at noon in Pau (120 miles in 30 hours), in my

opinion the prettiest town in the Pyrenees, and then after

necessary ablutions, hastened forth to see the famed Château

de Henri Quatre, generally called Henri le Grand.

Before I proceed farther, it may be well to give a short

sketch of the history of this castle. According to Froissard

this castle was erected by Gaston Phoebus, Count of Foix and

Prince of Béarn, about the year 1363. This nobleman built four

towers to which a fourth [sic] was added by Henri who was born

there, and whose cradle, an entire tortoiseshell, I saw under

a canopy placed there by order of Louis Quinze. The castle

suffered much during the revolution; the sculpture was defaced

and many souvenirs of Henri were totally destroyed. The cradle

even would have fallen a prey to the fury of an enraged mob,

if an individual had not taken it, and supplied its place with

another, which was soon dashed to pieces. All the rooms,

except that in which the cradle lies in state, are in very bad

preservation, being mostly without flooring. After returning I

dined at the table d’hôte, where the table groaned under a

multitude of dishes.

Pau, from France Pittoresque, 1835

During dinner I made acquaintance with a young German

who was travelling with his tutor, and in the evening I went

with him and some others to the Haras or stables where the

breed of horses is carefully kept up for the exclusive use of

the government. I saw some very nice horses there: a young

Arab in a paddock with its dam particularly attracted my

attention.

On the following morning, Thursday Aug. 23rd, I started for

Bagnères de Bigorre. On our way we passed through Tarbes, a

large town in the midst of an extensive and well watered

plain. After that we approached the Pyrenees, the sight of

which caused my heart to throb with a strange but not

unpleasing sensation. I felt proud at having mustered

sufficient courage to leave my friends behind me at the

distance of more than 40 leagues, and thus go without a guide

or even a companion at so early an age to throw myself among

strangers, and those foreigners.

Behind me was the fertile valley smiling under the rays of

a summer’s sun; before me were the black mountains towering

above thunder clouds still blacker, and which had in vain

attempted to overtop them. For a time I was lost in

admiration; but the sight of the lovely populous country

around me soon brought me to my senses. In a space of six

miles we passed through six villages containing good houses

some of which had beautiful gardens attached to them: in one

of these I observed a fine obelisk cut out of one entire piece

of marble.

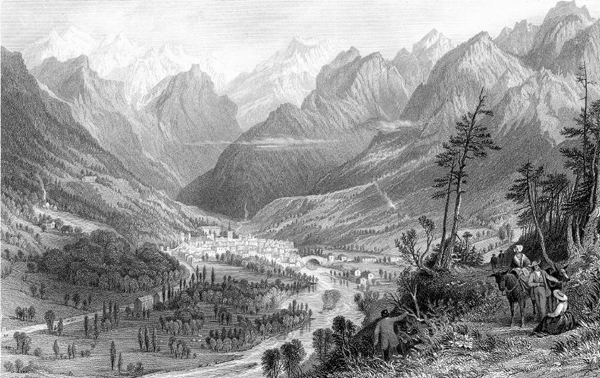

And now the mountains seem nearer and nearer, and now we

enter Bagnères de Bigorre which is nearly surrounded by their

giant forms, and soon I found myself seated at the Hôtel de

France, the principal hotel in Bagnères, before a good dinner

at 6 o’clock in the evening.

The next day, Friday Aug. 24th, I ascended a mountain which

overhangs the town to try my pistols. When on the summit, I

had full opportunity of observing the situation of the town

which lay at my feet. It is placed between the fertile

province of Bigorre and the luxuriant Vallée de Campan. I

could easily distinguish the stately buildings which are

erected over the mineral waters. Les Bains de la Reine, Les

Bains Caseaux, La Fontaine d’Angoulème are all famous in their

way for their wonderful cures. The houses in Bagnères are

excellent, and the streets are delightfully clean owing to the

numerous rivulets which descend from the mountains, so that

the town is very much resorted to by strangers.

And now behold me at 11 o’clock next morning, seated on a

very small poney, which I had hired for three francs a-day,

with my portmanteau and cloak strapped in due form before and

behind me, on my way into the mountains. I took the route

towards Tarbes until I reached the pretty village of

Montgaillard, when I turned short off to the left, following

the road to Lourdes. I now began to be surrounded by mountains

which by their black and frowning appearance announced

themselves to be the Pyrenees. And now I could see the castle

of Lourdes on a rock towering above the town, so I soon found

myself at the Hôtel de Poste refreshing myself after a hot and

fatiguing ride of ten miles.

However! No time was to be lost, my day’s journey was not

nearly done, so I jumped up and after a steep and circuitous

ascent gained the castle which completely commands all the

adjacent country. This fortress was formerly the residence of

the Counts of Bigorre and is of great age, having formerly

been attacked by our king John. It now has a garrison of 100

men with a few pieces of artillery. From the tower I could

discern four grand routes. Before me lay the road to Argelès,

behind me to Tarbes, that on my right led to Pau, and that on

my left to Bagnères de Bigorre which I had just left.

Having descended from the chateau, I mounted and proceeded

by the side of a foaming torrent called a Gave and through a

lovely valley to Argelès which is situated in a plain. After

Argelès the scenery began to be more terrible every moment.

Immense cliffs, to which St Vincent’s rock at the Bristol

Hotwells is but a cipher, overhung the right side of the road

covered with clouds : on my left the Gave de Pau foamed

impetuously by. After passing through several villages I

arrived at Pierrefitte, a small place about eight miles from

Cauterets. The night and drizzling storms were now falling

fast around me, so I rode on as fast as my jaded poney would

go, more intent about keeping him on his legs than admiring

the terrific and interesting scenery on either hand.

Wet and tired did I arrive at the Lion d’Or in Cauterets,

wet and tired did I pass the night; for my bed was very damp,

and the asthmatic groans of a sick man in an adjoining chamber

acted rather as the admonitory "il faut mourir, mon frère" of

the Trappistes than as an incentive to to sleep.

Cauterets, drawn by Thomas Allom, engraved by S. Fisher, c.

1850

On Sunday I attended the dog market which is

held weekly in Cauterets, the peasants bringing down these

animals from the mountains, when they descend to attend

mass. I bought a pup of the mountain breed

– véritable espèce

– for

six francs. I at first objected to him fearing that, from his

then appearance, he would never be very large; but my mouth

was soon stopped by a mountaineer chorus of "Mon Dieu,

Monsieur, il sera monstre" and certainly in aftertimes when I

watched him stalking majestically by my side far overtopping

all the dogs around him, like Agamemnon among his compeers, I

considered that I had no reason to repent of my purchase.

Cauterets, The Dog Market, card

postmarked 1905

Cauterets is entirely surrounded

by lofty mountains, consequently unapproachable by horses or

carriages except on the Pierrefitte side. It has three baths

all warm, the principal of which, La Raillère, owes its

discovery to a cow. I amused myself for an hour or two in the

forenoon by clambering up an adjacent mountain, and as I

toiled up a steep and difficult ascent a mountaineer passed

swiftly by closely followed by three goats. These animals,

frightened at the sight of a stranger, bounded up on a lofty

rock overhanging the path with incredible agility and then

darted down again, as soon as I had passed, to follow their

master.

Bath of La Raillère towards Cauterets

Aquatint

from Joseph Hardy, A Picturesque and Descriptive

Tour in the Mountains of the High Pyrenees,

London 1825

Next morning at ½ past five, accompanied by a guide who as

well as myself had in his hand a long pole shod with iron, I

set out for the Vignemale, the highest mountain of the French

Pyrenees, being 3356 metres = 10907 feet above the level of

the sea. Having passed the baths called La Raillère, we

arrived at the Cascade de Ceriziet [Ceriset], a picturesque

fall of about forty feet. It was after that that the scenery

became so majestically wild. This combined with the increasing

rarity of the air brought on a kind of delirium which I had

some difficulty in checking.

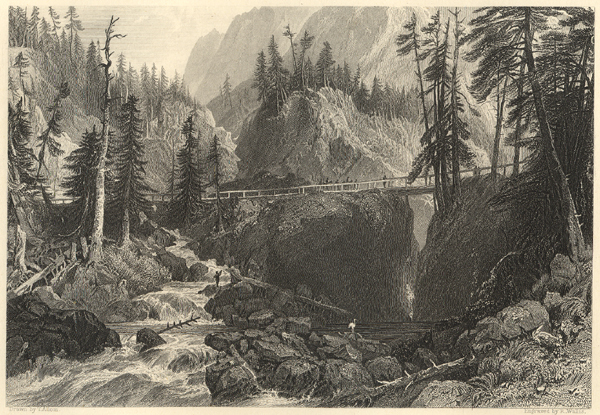

After passing another fine cascade called Boussès, we

arrived at the Pont d’Espagne, on which travellers have in

vain exhausted their descriptions. I stood upon a slender

bridge formed of the trunks of three of four pines negligently

flung across a chasm of 100 feet in depth under which the

Gave, after tumbling tumultuously down a precipice, rushed

furiously. The deafening roar of the wild waters, their greedy

rushing through the narrow bourn, the rocks, abysses and

wildnesses on all sides of me; all this, combined with the

sharp and clear atmosphere, produced such an effect on me,

leaning as I was over the frail parapet of the bridge, as I

certainly should not wish repeated under similar

circumstances.

Pont d’Espagne, drawn by Thomas Allom, engraved by R.

Wallis, c. 1860

After walking some distance farther

we arrived at the Lac de Gaube which is fed by mountain

streams that worm their way down the lofty steeps surrounding

it on every side. At the lake the scenery is very striking.

Behind me were mountains through the almost impassable paths

of which I had come; at my feet was the blue and deep lake

nearly motionless; on the right and left were lofty cliffs

which seemed to have risen out of the waters by enchantment,

and on the sides of which unscaleable by man I could see the

wild chamois bounding; and before me, towering above all, rose

the lofty Vignemale, his head enveloped with clouds and

everlasting snows.

Lac de Gaube, drawn by Thomas Allom, engraved by J. C. Bentley,

from France Illustrated,1840

My guide and I breakfasted on the banks of the lake hard by

an old fisherman’s cottage, the inhabitant of which has

resided there during the four summer months for the last 30

years. His name is Gaye, and he is 90 years old; nevertheless,

he rowed us over the lake with the agility of youth. Having

crossed, we bent our steps towards the Vignemale. The scenery

now began to change: the space between the mountains on either

hand became wider and was completely choked up with immense

stones which descend from the mountains in spring at the

melting of the snows.

At noon we arrived at the glacier of the Vignemale and

walked over the snow which was very hard. After writing your

name, my dear, on the enduring snow with the iron point of my

staff, I sat down on the ground and partook of the contents of

the guide’s wallet. Seldom does it befal mortals to have such

superb witnesses to their repasts as it then befel my guide

and me. Before us were the three peaks of the Vignemale, the

highest of which inaccessible to mortal footstep was

surrounded by mist. On our right and left were two lofty

cliffs: over the left height is carried the path which leads

into Spain whence we were not many miles distant. The valley

in which we were was full of desolation: no verdure, no trees,

no water; but instead a chaos of huge rocks rent by

convulsions from the neighbouring heights, and paving the

surface of the earth, huge and unequal.

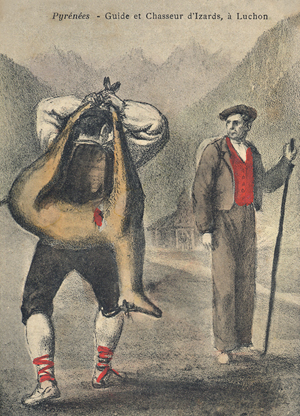

| We saw herds of chamois sporting over the snow; shortly

afterwards there was the sharp crack of a rifle, and presently

a huntsman appeared with his prey, an izard (for thus is

called the wild goat of the Pyrenees) slung round his neck.

These izards are much smaller than a goat with large sharp

horns very crooked: they are wonderfully fleet. We now

returned by the same way that we came and arrived at the inn

at ½ past five, having walked during twelve hours with

scarcely any intermission. |

|

Guide

and Izard Huntsman

Card

postmarked 1905

|

At break of next day I set out for Luz which place I

attained by noon after passing among some glorious scenery.

After breakfast I set out to see the famous Cascades de

Gavarnie, an excursion carefully to be remembered by me, since

my life on that day was in the most imminent peril. I ought to

have had a guide which precaution I neglected. I was wrong too

in starting so late in the day, for travellers usually start

for these cascades at eight in the morning. I soon left on my

right the pretty village of St Sauveur, and struck into a path

so dangerous, surrounded by scenery so wild that I shuddered

to pass it in the day, little thinking that it would be so

soon my fate to grope my return in the blackest night.

Luz & St Sauveur

Drawing by E. Paris, lithograph by Thierry Frères, Paris,

from the mid-1800s

The path for the whole distance (nearly 14 miles) was cut

out of or rather over huge masses of slippery rock. It was not

above four feet in width, having on one side an abrupt

precipice of 300 feet in depth at the bottom of which bounded

onward an impetuous Gave, and overhung on the other side by

rocks equally high. The scenery became more stupendous as I

advanced. The path repeatedly wound round huge masses of rocks

as big as palaces which had been torn from the adjacent

summits; and in the distance I could discern with difficulty

some towering peak wrapped round with mist.

Le Pas de L’Échelle, the route from

Luz St Sauveur to Gavarnie

Depicted and lithographed by Julien Jacottet, Paris c.

1840

At five in the afternoon the cascade of Gavarnie broke upon

my sight. To find words to describe what I then saw would be

impossible. You must imagine, my dear , a vast sheet of water

precipitating itself down a height of not less than 1266 feet

and boiling in the basin below. The clouds which floated about

amidst this vast amphitheatre of rocks gave an unearthly

appearance to the scene. Æschylus might have chained his

Prometheus to one of these lofty summits without detracting

from the sublimity of his wonderful tragedy.

Cascade de Gavarnie, from France

Pittoresque, 1835

I now turned my poney’s head

towards Luz. A rain was falling from the mist, but it was

still light when I arrived in two hours and a half at

Gavarnie, a small and miserable hamlet situated halfway

between the cascades and Luz. I had now seven miles of the

most dangerous part of the journey to travel over, and before

I had lost sight of the village, darkness came on. I was then

stopped and questioned by one of the gendarmerie which made me

later. Another mile and I could not see my poney’s head, for

the rain fell heavily, the night swiftly, and the mist

thickly. I had three bridges to cross, two of which were of

the rudest description. I passed one bridge, but I should not

have known that I was passing it, if the noise of the Gave

beneath had not outsounded the elements. As I was spurring the

poney to pass over the second, two huge dogs sprang out from a

cleft in the rock and jumped up at me barking loudly. These

were soon followed by their master, some shepherd with a

lantern who lighted me over the frail planks.

As I continued my journey, I could feel (seeing was out of

the question) my foot brushing the bushes which overhung the

precipice. By and bye the poney stopped conscious of the

danger and not able to see the way. This much dispirited me as

I had for some miles been trusting myself entirely to him.

However, after commending myself to Providence I urged him on,

and we proceeded for some distance. He stopped again, and

refused to go any farther. I dismounted that I might grope the

way on foot, and slipped so that I found myself sitting with

my two feet hanging over the edge of the abyss. The Gave

seemed to laugh exultingly at receiving a fresh victim, for

many had fallen into the torrent never to return, but the

poney hearing me slip as I fell was startled and pulled me

back by the bridle which luckily I held tightly, so I struck

off in another direction which proved the right.

After proceeding a long way, every moment expecting to slip

over the cliff, which catastrophe the poney adroitly eluded,

how great was my joy to perceive the lights of St Sauveur. I

then knew that I was but a quarter of a mile of good road from

Luz: however, the only accident which happened to me at all

was between these two places. As I was cautiously leading my

poney along, I fell into a sort of ditch nine feet deep and

should have pulled him over me if the bridle had not slipped

over his head.

Wet frightened and scratched, hungry and sleepy I entered

the town of Luz at ½ past ten at night. Not a light was in any

of the windows, and my late adventures had totally obliterated

from my memory all traces of the whereabouts of my hostelerie.

Once more I trusted to my poney; I got on his back, threw the

reins on his neck and ere long stood before the inn where I

astonished the inmates with an account of my excursion.

Next morning I proceeded to Barrèges, a town much more

celebrated for its waters than its fine buildings. It was then

exceedingly full of company. From Barrèges I struck into a

path leading over the Tourmalet, a chain of mountains which it

is necessary to cross in going to Bagnères de Bigorre.The

scenery on the vast ridges of the Tourmalet was wild and

desolate, the track tedious, lonely and difficult. When,

however, I had ascended a cloud-capped mountain, I began

rapidly to descend into a valley completely filled by a dense,

white mist which emitted a heavy shower.

Le Col de Tourmalet, the route from Barèges to Bagnères

de Bigorre

Depicted and lithographed by Julien Jacottet, Paris c. 1840

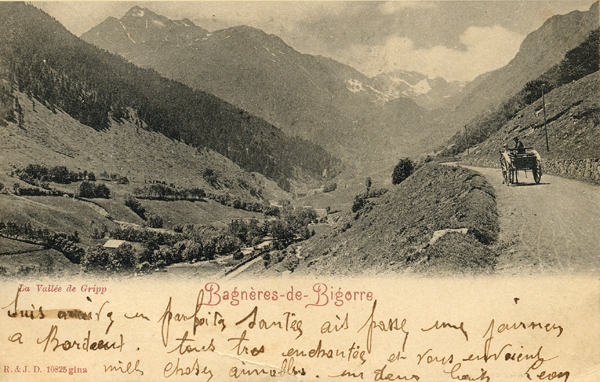

After a very uncomfortable journey, owing to the rain [and]

the fear of being benighted in a country where, if I had

missed the slight track on which I depended, I might have

wandered several days without seeing anyone, owing too to the

fatigue of my dog which I was frequently obliged to fling over

the saddle whilst I walked, Gripp was at length gained, a

village consisting of numberless cottages, each situated in

the midst of its own meadow. Night forced me to stop there,

although Bagnères was only six miles distant, so I surrendered

myself to the excellent accommodation of the Hôtel de Gripp.

The Gripp Valley, card postmarked 1901

Next morning rising with the sun, which promised a lovely

day, I started for Bagnères, my road lying through the

charming valley Campan. I was accompanied to the nearest

village, St Marie, I think, by the landlady’s daughter, a

pretty child of 10 years of age who, mounted on a donkey, was

going to buy bread. She beguiled the way by telling me a

wonderful story of a monster which like the dragon of Rhodes

had devastated the country of late. According to her this

creature was immensely large, and had the body of a bear with

the head of a bulldog. It had eaten three weeks before four

horses, seven cows and, to crown all, an old woman. She added

that on the following Sunday after mass there would be a

general hunt to take and kill the brute.

And now the lovely valley became more lovely every moment.

The green and luxuriant pastures speckled with innumerable

cottages and beyond these the many peaks, whose eternal snows

glittered like silver in the sun, made a fine contrast with

the black and barren rocks which frowned on the opposite side.

At 10 o’clock on Thursday the 30th of August I arrived at

Bagnères having been absent on my mountain excursion during

five days.

On Sunday I went to Gripp with an Englishman to see the

monster hunt, but we found that it had been deferred until the

Sunday following, so we went on to the Pic du Midi which is

only to be surpassed in height by the Vignemale being 2973

metres = 9662 feet above the level of the sea. The extreme

heat of the day prevented us from ascending, so we contented

ourselves by contemplating its vast proportions. It seemed a

vast rock and is exceedingly steep requiring three hours to

ascend and two to descend. We sat down on the grass and

conversed with three old shepherds: when we [were] about to

depart my friend gave them 30 sous between them. They were so

amazed at this generosity that they wished to return half. On

our return to Bagnères in the evening we encountered troops of

young villageoises who, clad in picturesque costume, came to

offer bouquets of choice flowers.

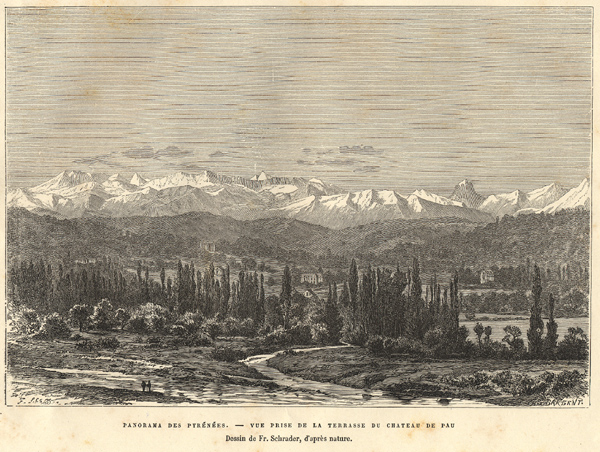

Monday saw me arrived at Pau where circumstances compelled

me to stay until the Thursday following. The more I saw of Pau

the more I was enchanted with it. I prefer it much to the

towns in the centre of the Pyrenees. The distant view of the

Pyrenees as seen from Pau pleases me more than the black

mountains or rather rocks which overhang Bagnères and

Cauterets.

Panorama of the Pyrenees as seen from Pau, c.

1880

Pau possesses five promenades two of which are

truly charming: one is in the middle of the town; the second

is higher up and is chiefly used by the military. Another is

from the terrace of the chateau whence is to be seen a lovely

river rolling through the plain below; beyond that lofty yet

luxuriant hills, and much farther still, so enveloped by

clouds that at first view they might be mistaken for clouds,

the black Pyrenees. The fourth is by the side of a small

stream which hastens to throw itself into the river. The last

is by the side of the limpid river which may be seen filled

with carts drawn by oxen, whilst the drivers are busily

employed in loading them with stones, which they pick up from

the bed of the stream.

On Thursday the 6th of September I started for Bordeaux

where I arrived on Friday morning (my birthday, being 16 years

of age) safe and sound, thank God, after laughing heartily all

the way, there being in the same part of the Diligence as

myself all sorts of animals, as a man remarked, English,

Gascons, Parisians, French poodles, 2 huge Pyrenean dogs,

squirrels and ferrets. The odour arising from such a

congregation was not, as you may suppose, the most

agreeable.

|