Mereweather loved Venice, its cultural heritage, its beauty. Semele of Greek mythology is turned into

an orphan daughter of noble Anglo-French lineage. She explores

the city and the lagoon giving the reader something of a

guided tour. After her wish to see the Spirit of all Beauty is

granted, she goes mad; she dies a few months later. The book,

which impressed an Italian reviewer, became something of a

guide to Mereweather's own inner struggle "loving Beauty and

Art, Spirit and Embodiment, with a frenzied enthusiasm,

excluding all rational consideration of human duties and

every-day life" (Semele, p. x).

One source of inspiration is the Swedish

mystic Emanuel Swedenborg. In his Memorable Relations

Semele "read how a too sensitive, or rather diseased,

imagination carried the writer into the realms of spirits; and

how at pleasure he could invade the Blissful Land".

(Semele, p. 17)

The set-up can be boring: the Spirit is

the poetical cicerone of Semele who, in turn, is guiding the

reader. Nevertheless, the book is full of cultural, historical

and linguistic details, including an interesting description

of the tableland of the Sette Comuni in the province of

Vicenza. Click on the Sette Comuni link

above.

See below for some extracts.

Various illustrations have been added.

Riva degli Schiavoni,

from Ponte della Paglia

Photograph, probably by

Paolo Salviati, c. 1870

"When Semele first arrived at Venice, she took up her

residence at a large hotel on the Riva degli Schiavoni, once

belonging to the family Bernardo, built in the Pointed style

of architecture at the beginning of the fifteenth century.

Under her windows ran a spacious quay, crowded with people

clad in a variety of costumes, and speaking a diversity of

tongues." (Semele, p. 35)

San Giorgio Maggiore

Photograph by

Christer Björkvall, c. 1955

"Before her, as she stood on the balcony, lay the

island of St. Giorgio Maggiore, once, in very old times,

crowned with cypresses, and refreshing the eye with its

verdure; now groaning under the weight of a Renaissance

church, barracks, and artillery." (Semele, p. 35)

Inspecting Venice

In a gondola Semele

"floated

along off the Riva degli Schiavoni, rendezvous of innumerable

‘trabaccoli’, two-masted coasting vessels, from the Dalmatian

and Istrian ports. She then passed the south entrance to the

arsenal, the ‘Arzanà de' Viniziani’ of Dante, rounded the

Giardino Publico, rowed under the interminable wall which

bounds the north side of the arsenal, and pursued her course

along the Fondamenta Nuove, having on the right the Cemetery

and Murano, that once renowned island, peopled, in times long

passed, by fugitives from Hunnic and Lombard ravagers, and

later, birthplace or favourite haunt of many learned

spirits,—island, whose glass manufacturers' daughters were

considered worthy to mate with Venetian patricians. Thence the

gondola coasted along by the Campo di Marte—drillground for

Austrian troops—and soon arrived in the canal of the Giudecca

off a Fondamenta called ‘Le Zattere’, once crowded with

charcoal-laden rafts. And then she passed down the Grand Canal

and the Canareggio, and afterwards returned by the same route

to her starting-point. Thus Semele, by this tour of

superficial inspection, could comprehend the plan of Venice,

and judge of the site where she would be most pleased to

reside."

(Semele, p. 36)

The Madonna

dell'Orto area

Semele "fixed her residence in a large palace [Palazzo

Contarini dal Zaffo] at the

northern extremity of Venice near the church of Our Lady of

the Garden [Madonna dell'Orto]. The view from the balcony of

the first floor, or Piano Nobile, of this palace was a thing

of enchantment. Below was a fertile garden rich with gay

flowers and intersected by straight alleys sheltered from the

rays of the sun by vines trained on trellis-work. Fig, almond,

peach, and pomegranate trees were studded here and there,

whilst some funereal cypresses toned down the laughing scene

around. To the garden succeeded an extensive grass plot,

having in the midst a large, empty basin of stone, presided

over by some colossal water-deity, attitudinizing in all the

mannerism of seventeenth-century art. This lawn terminated in

a balustrade slightly raised above the level of the lagune,

the waters of which caressed its base with their ripplings.

About a mile away in front, couched upon the mirror-like

sea, lay the island of Murano, rich with fair gardens, and

displaying its two massive church towers, one uncrowned with

cupola. To the right of Murano, and about half a mile apart

from it, gleamed in the clear atmosphere the church of San

Michele and the walls of its adjoining cemetery; ... ... Three hundred years before, great and ingenious minds

such as Titian, Sansovino, Navagero, Pietro Aretino, and

Sanmicheli were wooed to recreate in this favoured spot; and

in a spacious mansion near, since called Il Casino degli

Spiriti, probably germinated those flashes of genius and

triumphs of art which have illustrated the Italian name

throughout all lands." (Semele, p.37ff). Click on the

Venice Map link above.

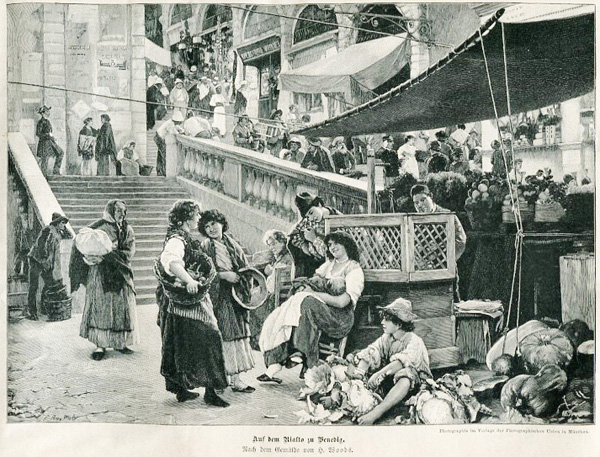

On the Rialto in Venice

After the painting by H. Woods

Published by Die Photographische Union in Munich, late

19th century

And soon Semele "arrived at the Ponte di Rialto, the

majestic proportions of which are destroyed by the

twenty-four shops which cloud and encumber the superjacent

arcades. (Palladio, Michel Angelo Buonarotti. Sansovino,

Scamozzi, and Fra Giocondo sent in models and plans for

this bridge. Those of Antonio dal Ponte were chosen, not

because they were the best, but because they were the

cheapest.) … … … And afterwards she descended the Bridge

of the Rialto, and at the bottom, looking behind her,

observed the people ascending and descending the stately

triple staircase, putting her in mind of a dream dreamt at

Bethel in times long past, save that the angelic natures

were wanting." (Semele,

p. 43ff)

The poor

"In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries the population of

Venice was nearly three hundred thousand, and the poor were

prosperous, because fully occupied either as servants of the

great families, or as employed in the vast commerce which

flowed into this mart of nations. Besides this, their

physical welfare was carefully promoted by the powerful

Proveditori del Comune created for that purpose. These

officers arranged that the food of the working population

should be of the best and cheapest, and above all, they

restrained by severe laws severely carried out, the vendors

of necessaries from imposing on the poor. But now, Semele

found that the population was reduced to less than a hundred

thousand souls, and that the lower classes were no longer

prosperous, but miserable; for no rich houses fed and lodged

a crowd of gondoliers and servants, nor did the Port and

Arsenal give work and wages, as of old, to hungry

multitudes: nor were there any Proveditori to protect the

people from the over-charges and trickery of the bread,

meat, and wine sellers; whilst the innumerable charitable

and mutual aid societies once flourishing, had disappeared.

Consequently, thousands upon thousands were dependent for

their wretched existence on extraneous aid. And yet they

were good-tempered, courteous, intelligent, and even

disinterested, at least those who had not been brought in

contact with foreigners." (Semele, p. 47f)

Scala Contarini del

Bovolo

"During one of her walks, Semele discovered in the most

labyrinthine of labyrinths, in the Calle e Corte del Maltese

detta del Risi, leading out of the Calle della Vida, which

leads out of the Calle delle Locande, which must be approached

from the Rio Terrà di S. Paternian, close to the Campo of that

name, a circular staircase of exquisite geometrical

proportions, twenty-two feet in diameter, seventy in height,

and surmounted by a cupola which protects the whole from the

weather. This capo d'opera entirely constructed of Istrian

stone, is the production of an unknown architect of the

fifteenth century; and was probably constructed as a splendid

caprice, to act as an outer staircase to a palace more ancient

than the one it now adjoins. The whole structure breathes of

solidity and quaint grace, and fully merits its title of La

Scala Formosa." (Semele, p. 49) |

|

|

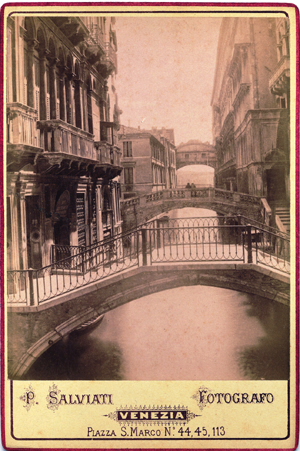

The Bridge of Sighs

Rio di Palazzo towards the

lagoon with Ponte dei Sospiri, c. 1880

The view of Ponte della Paglia

is obstructed by Ponte della

Canonica |

"And then she walked to and fro on the Piazzetta, between

the Giardinetto, or Royal Garden, and the Ponte della Paglia,

close over which loomed in the darkness the Ponte de' Sospiri,

built in 1591, after the plans of Antonio da Ponte the

architect of the Rialto Bridge. This closed bridge she was

informed, was divided longitudinally by a partition wall, the

passage to the south leading from the department of the

Avvogadori del Comun to the prison; that to the north,

connecting the prison with the Tribunal of the Ten. For in

Venice all was suspicious precaution and secrecy and

accordingly it would not have been meet that the prisoners of

the Council of the Ten should have been mingled in their

gloomy transit with those of the Avvogadori." (Semele,

p. 56)

| The

Arsenal

"Some days afterwards, Semele went early to the

Arsenal, ... ... In this vast group of buildings,

founded in 1104, and gradually increased to their

present extent, not many objects were found to interest

the feminine sensibilities of Semele. Four animals,

which her guide called lions, and eight others which he

named Pagan Deities, these monstrous specimens of

depraved renaissance art, and those monstrous

specimens of expiring Grecian art, sentinelled the

entrance to the ‘Arsenal of the Venetians’. The largest

of the lions, however, attracted her momentary interest

by the strange characters, probably of despairing

illegibility, traced upon his body. Whether they were

Pelasgic, or Greek, cotemporary with the battle of

Marathon, or Runic, or old Saxon chiselled for amusement

in the tenth century by the Varangian Guard of the

Emperors of Constantinople, no one could tell her.

Certain it was that they all came either from the

Piræus, or the road leading thence to ‘Town’, τό ’Άστυ, or from

somewhere else in Attica, for they were brought from

Athens in 1687 by Francesco Morosini during his

occupation of Achaia." Semele, p. 65ff) |

|

| The Island of San

Lazzaro

"From the Public Gardens Semele's gondola with its

four stalwart rowers swiftly flew over the still surface

of the lagune towards the island of San Lazzaro, once,

in 1182, a refuge for lepers; now the abode of Armenian

monks of the order of S. Benedict. And she was

courteously conducted over the domains of this

intelligent and gentle-mannered brotherhood, and shown

their church, and library of 14,000 volumes and 1,400

Armenian manuscripts, and their admirable

printing-press. There she saw some monks of extreme old

age, with very white beards; and all received her

cheerfully and kindly." (Semele, p. 71) |

|

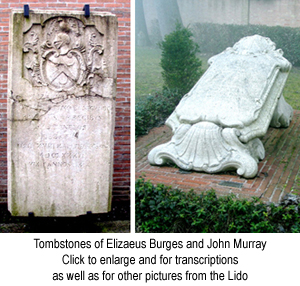

| The Lido

Semele "pursued her way to the Lido, and wandered

through waste places, rendered still sadder by

monumental memorials of Protestant and Israelite. But

over all this desolate scene, the lark, blithe spirit of

the islands of the lagunes, sang sweetly, as it had been

the soul of one of the entombed, guarding its mortal

remains. And she deciphered inscriptions on the

tombstones of British envoys and consuls ..."

(Semele, p. 71)

|

|

| From the

Lido

"The night damps were falling, the moon was hastening

towards her western goal ... ." So Semele "left the

Lido, and bent her course towards home. And on her way

she heard voices in a distant boat singing one of those

exquisite barcaroles, so full of soft plaintive melody,

which are peculiar to Venice. It was ‘La Barcheta ze a

la riva’, and so perfect was the harmony, and gracefully

simple the melody of this canzonetta, that the silvery

notes fell like a musical dew upon the surrounding

waters and lulled with their liquid influence the hearts

of the hearers into a half-waking trance, so saturating

their souls with soft music, that the internal echo

ceased not long after the singers were out of of

hearing." (Semele, p. 80f) |

|

View from San

Giorgio across the Bacino di San Marco

Photograph by Paolo Salviati, c. 1880

"… one bright morning, Semele ordered her gondoliers to

conduct her into the mid-channel between the Church of S.

Giorgio and the Piazzetta. From thence the marvellous view

of the south side of Venice glowed before her. There was the

busy Riva degli Schiavoni laid out in all its sunny

splendour, until it merged into the massive verdure of the

Public Garden; the dark prison; the darker Bridge of Sighs;

the Ducal Palace, marvellous union of massive solidity with

graceful airy lightness, fair type of the junction of soul

and body; the southern portion of S. Mark's, inexplicably

rich in oriental marbles; the quaint tower of the Clock, the

two Columns, the Library, the Mint, the Imperial Palace and

Gardens, the lordly entrance of the Grand Canal, sentinelled

by the majestic church of the Salute; whilst on her left

sparkled the waters of the Canal of the Giudecca, with its

forest of masts. Over all, the radiant angel hovering on the

apex of the pyramidal termination of the gigantic Campanile

of S. Mark, seemed to give his benediction." (Semele,

p. 93)

The Accademia bridge, built in 1854 by

the Austrians (demolished in the early 1930s)

Card

postmarked 1911, view towards la Dogana

Semele slowly glided over the limpid waters of the Grand

Canal from Punta della Dogana. "Then she rowed by the spot

soon to be desecrated by the most hideous of bridges

constructed by an English engineer, with a sense of beauty as

hard as the iron he employed in his work." (Semele, p.

95)

Il Fondaco dei

Turchi,

Restauration of the façade on the Grand Canal

Wood engraving by E. Roevens and A. Deroy, published in Le

Monde Illustré, 1869

"And a little

farther on, at the left hand, the long double ranges or

tiers of elegant Byzantine arches belonging to the Fondaco

de’ Turchi, work of the eleventh century, rose like a

pleasant dream. Most beauteous and rare in its semi ruin

this Oriental structure appeared to the eyes of Semele,

although the costly marbles which once incased it had long

since been torn away. And she reflected that this costly

edifice, work worthy of advanced civilization, stood in all

its unmutilated exquisite proportions at that remote epoch

when in England the Saxon Ethelred was treacherously

slaughtering Danish residents; when Sweyn, the fierce King

of Denmark, was seizing the English throne, amid the wailing

and execrations of massacred Saxons; and when Scotland

trembled under the usurping rule of the sanguinary Macbeth;

and that even then the tides of the Lagunes bathed the walls

of a city which could calculate its existence by centuries.

She cared not to hear that it once belonged to the Pesaro

family, and was by them ceded to the Government in 1380, who

presented it to the Duke of Ferrara; that it went into the

possession of Michele Priuli, bishop of Vicenza, and

afterwards was appropriated as the abode of the Turkish

merchants visiting Venice; but she did care to hear that the

Duke Alphonso of Este was once lodged here, and brought with

him his friend Torquato Tasso, that translucent fount of

limpid verse." (Semele, p. 100f)

Mazzorbo

Steel engraving by C. Heath after a picture by C. Stanfield,

Longman & Co., London, c. 1840

From Burano

"passing over a long and narrow wooden bridge, she arrived

at Mazzorbo, the ancient Majurbium, formerly an island

faubourg of Altinum. This once populous island, anciently

the resort of Venetians during the summer season, had in old

times contained five parishes, numerous monasteries, and ten

churches. Now it was almost deserted, numbering but a few

inhabitants, who by their labour developed the indescribable

fertility of its gardens and orchards. And when Semele

recounted to her companions the melancholy feeling that

pervaded her as she trod on this desolate ground, formerly a

centre of civilization, she was reminded that these Lagunes

once possessed at least thirty islands, centres of religious

or secular interest, which are now either mournful swamps

inhabited by wildfowl, or entirely covered by the

treacherous waves, showing at low tide fragmentary ruins of

early civilization, or mediæval piety. They told her how

Costanziaca was once rich in many highly decorated churches,

now sunk beneath the surrounding hungry swamps; and how S.

Catoldo, anciently the seat of the Episcopal Seminary of

Torcello, was now but a slimy ridge, scarce rising above the

level of the waters, called by the vulgar Monte dell'Oro,

because, so they say, the golden car of the grim Attila, and

his other treasures, were buried there. So pondering over

these ruins of time, and reflecting how not only the

heavenly bodies, but indeed all earthly things seem to roll

unceasingly, never tranquil, round an immovable centre,

ending where they set out,

…" (Semele, p. 108f)

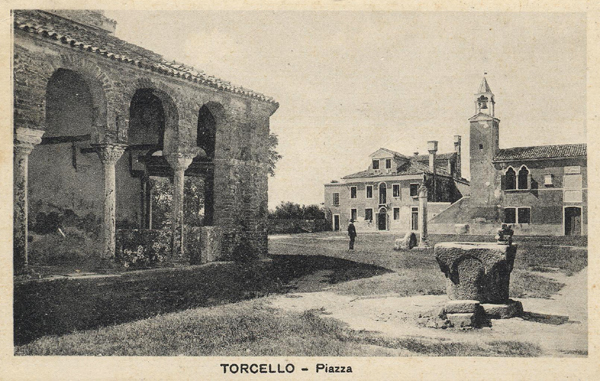

Torcello, the Piazza

Small size

postcard, c. 1910

"... Semele landed on the grass-covered Piazza of the once

superb Torcello. Here indeed she found proof upon proof of

time's vicissitudes. Could this unpeopled waste, approached by

a stagnant canal hardly restrained within its crumbling banks;

these melancholy fever-stricken gardens without cultivators;

this group of churches without worshippers, have ever been

populous, rich, and magnificent, radiant with marble palaces,

the new Altinum, rival of the old? ... ... Yes! This mockery

of a Piazza, glaring forth its poverty and neglect, was once

the centre of a rich and flourishing city, existing from a

remote period, as the old Venetian, Lombard, Hunnish, Roman,

and Grecian coins, frequently found beneath the soil, attest.

... ... But, alas! owing to the changed course of the waters

of the river Sile, fever was produced in this once favoured

spot; and then little by little the inhabitants decreased; so

in time it ceased to be a Bishop's see, the monasteries were

dissolved or transferred elsewhere, and thus by easy

gradations it descended to its lamentable state of present

perdition – its handful of cottages, its fifty or sixty

denizens. And there in the Piazza, in front of a barn and

granary, once a loggetta, from whence were proclaimed the laws

of the Republic and the Municipality, probably the remains of

the palace of the Podestà, Semele saw a rude stone chair,

popularly called "the Chair of Attila", whence the early

tribunes used to minister justice. She paused before the two

churches, the Duomo and Santa Fosca, each of surpassing

interest in its way, and carrying the observer back to the

remotest ages of Christian architecture." (Semele,

109ff)

Chiesa di San Pietro di Castello

"On the left hand, as one enters this church, there is to

be seen a very curious old tombstone, covering a vault, which,

as we learn from the inscription, belonged to the gondolier

fraternity at that ferry over the Grand Canal which is called

the Traghetto di San Barnaba. The inscription (in old

Venetian) runs thus:—

‘In tempo de Zorzi da Cataro

Gastaldo del

Tragetto

De San Barnaba

Et Nicolo de Zorzi

Et Migiel

de Bernardo

E. Compagni L. Anno

MDIII.’

Then follows a rude representation of a boat, something

like this:—

This is the church "of S. Pietro di Castello, containing,

as legends tell, the marble chair in which S. Peter sat at

Antioch". (Semele, p. 121f & note 5)

The Colleoni monument

"In the open space of ground adorned by the façades

of the Gothic church of SS. Giovanni e Paolo, and the

Scuola di San Marco, long changed into a Civil Hospital,

stands the equestrian statue of Bartolomeo Colleoni,

Commander of the Venetian land forces in the fifteenth

century, and the first artillery captain of his age.

This military chief, a Bergamasque by birth, left as a

legacy to the Republic, not only a hundred thousand gold

ducats, and the third part of ten thousand ducats due to

him from the Duke of Ferrara, but also all his arrears

of pay, with a request attached to his testament, that

an equestrian statue in bronze should be raised to his

honour in the Piazza di San Marco. The Senate accepted

the legacy, but departed from the wish of the donor by

erecting the memorial in the Campo de SS. Giovanni e

Paolo. There it has stood from the year 1495 with the

following inscription: 'Bartholomeo Coleono Bergamensi

ob militare imperium optime gestum. S. C.' ... ... ...

There was the successful soldier, in hardy daring

attitude sitting on his war-steed, more in the guise of

command than of good horsemanship, with his feet

stretched out before him almost scorning the assistance

of the stirrup. Under him, full of life and strength and

energy, and, luckily for the rider, thoroughly trained,

paced in quick walk the noble well-formed steed, so

life-like, that the pedestal seemed too short for the

step that he was certainly about to make."

(Semele, p. 128ff) |

Winter

"One bright

morning Semele walked on the terrace washed at its base by

the laughing daughters of the Adriatic. On her left the

terraced Alps reared themselves into the ether, commencing

with the fertile verdure-covered declivites descending into

the plain close to Conegliano, and ending with inaccessible

spirelike Tyrolean dolomite rocks. The sharp air of the more

early hours of the day at that advanced season had yielded

to the Italian sunshine; the night-mists had passed away,

and a most clear atmosphere rendered all distant objects

visible with a startling distinctness seemingly unreal to an

inhabitant of cloudy climes. And the leaves of the trees in

the many gardens of Murano were changing colour in

anticipation of the approach of winter with all its

severity*;" (Semele, p. 131ff)

"

* Let no one think that Venetian winters are devoid of

cold. What with the occasional Bora (Boreas), blowing from

the north-east over the snow-covered Alps, its girdle of

water, and its total absence of those endless appliances

which in northern regions regard animal comfort, Venice,

during the greater part of the months of January and

February, is practically one of the coldest places in Europe

to reside in. In January, 1858, the author saw the whole

Lagune frozen thickly over between Venice and Mestre, the

thermometer falling to 12° below zero (Réaumur) [ -15° C].

In other winters, the small canals in Venice are frequently

frozen over. Whilst these frosts last, the nights feel

milder than the days, during which, in spite of a good stove

in the sitting-rooms, the pen will fall from the numbed

fingers of the writer, shivering under a freezing

temperature. Perhaps the following notes of extremely cold

seasons in Venice will not be uninteresting to the reader.

[Here follow comments on the severe winters of the years

568, 852, 1118, 1413, 1419, and 1431 when] a frost commenced

the 6th of January, and lasted until the l2th of February,

during which interval a bride came from Mestre in a carriage

over the ice, bringing her dowry with her, [as well as 1486,

1514, 1548, 1549, 1598, 1601, 1608, 1684, 1709, 1716, 1740,

1758, and 1788-1789 when] the Lagunes were frozen over from

the 28th of December to the 24th of January, and a road was

kept clear to Mestre, by which passed all the heavy and

light traffic, and public-houses and amusements were rife

upon the ice. On the night of the commencement of this frost

many people died of cold in the streets, the houses, and the

cafes."

Isola San Francesco del Deserto,

c. 1900

One night at "half-past nine Semele ordered her gondola

with four rowers to be prepared to take her to the island of

S. Francesco nel Deserto." (Semele, p. 153) "... she found her

way into the half-ruined, desecrated church, and kneeling

close to the narrow cell where S. Francis used to sleep,

poured forth thanksgivings for having attained the object of

her fondest hopes. Thence she passed into the open space,

where was a rude hut, in which the venerable saint used to

pray, now almost filled up by the lower part of the trunk of a

large cypress tree. Then she, led by some mysterious impulse,

moved joyfully and fearlessly forward into a large piece of

ground at the back of the convent, looking towards the swampy

shores of Erasmo, on the other side of which chafed the

restless Adriatic. In the middle of this space grew five tall

cypresses, so grouped together, that the largest stood in the

centre surrounded by the four others. Against this tree she

leaned, awaiting with fond confidence the arrival of the

object of her strange and passionate love

– her sense of the

Beautiful accurately shaped forth in intensest concentration.

The rain and wind had ceased, but the black cloud remained,

and every now and then the vivid lightning laid open its lurid

recesses, leaving every thing blacker than before. And then

Semele, with hands erect, as one earnestly praying, said, 'O

glorious Spirit, that fillest the universe with thy presence,

behold me here, unceasing seeker of thee in visible form! Be

present now according to thine infallible promise, and afford

me, at least, one glance of thy divine attributes, thus

satisfying the life-long cravings of a heart and brain, which

would comprehend in one vivid concentration all the infinite

beauty of the material universe.'" (Semele, p.

159f)

Further reading: P. Bernardino Barban,

L'Isoletta di "S.

Francesco del Deserto" nelle Lagune di Venezia,

Vicenza 1927.

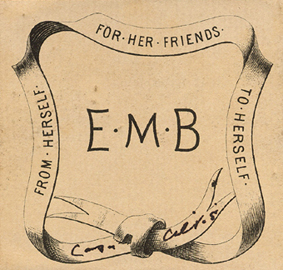

On the inside of the front cover

of the Semele copy depicted above, there is a

bookplate:

E · M · B

FROM · HERSELF ·

FOR · HER · FRIENDS ·

TO · HERSELF ·

Casa Alvisi

[Venice]

This would be Edith Millicent

Bronson. She was born in Newport, RI, USA, in 1861. In 1895

she married Count Cosimo Rucellai, Florence.